Football tactics is what originally swayed me in the direction of football analysis. I’m a sucker for patterns and causal relationship, sos when I was introduced to football tactics, I was completely emerged and sucked into the world of tactical analysis.

A few years later, I ran into a quite common problem: data vs. eyes. I have mostly focused on data lately, and that’s what I work with. In other words, right now, I work as a data engineer at a professional football club, where I don’t really focus on any aspect of video. The problem arises that for tactics, we mostly use our eyes because the data can’t tell us why something happens at a specific time on the pitch.

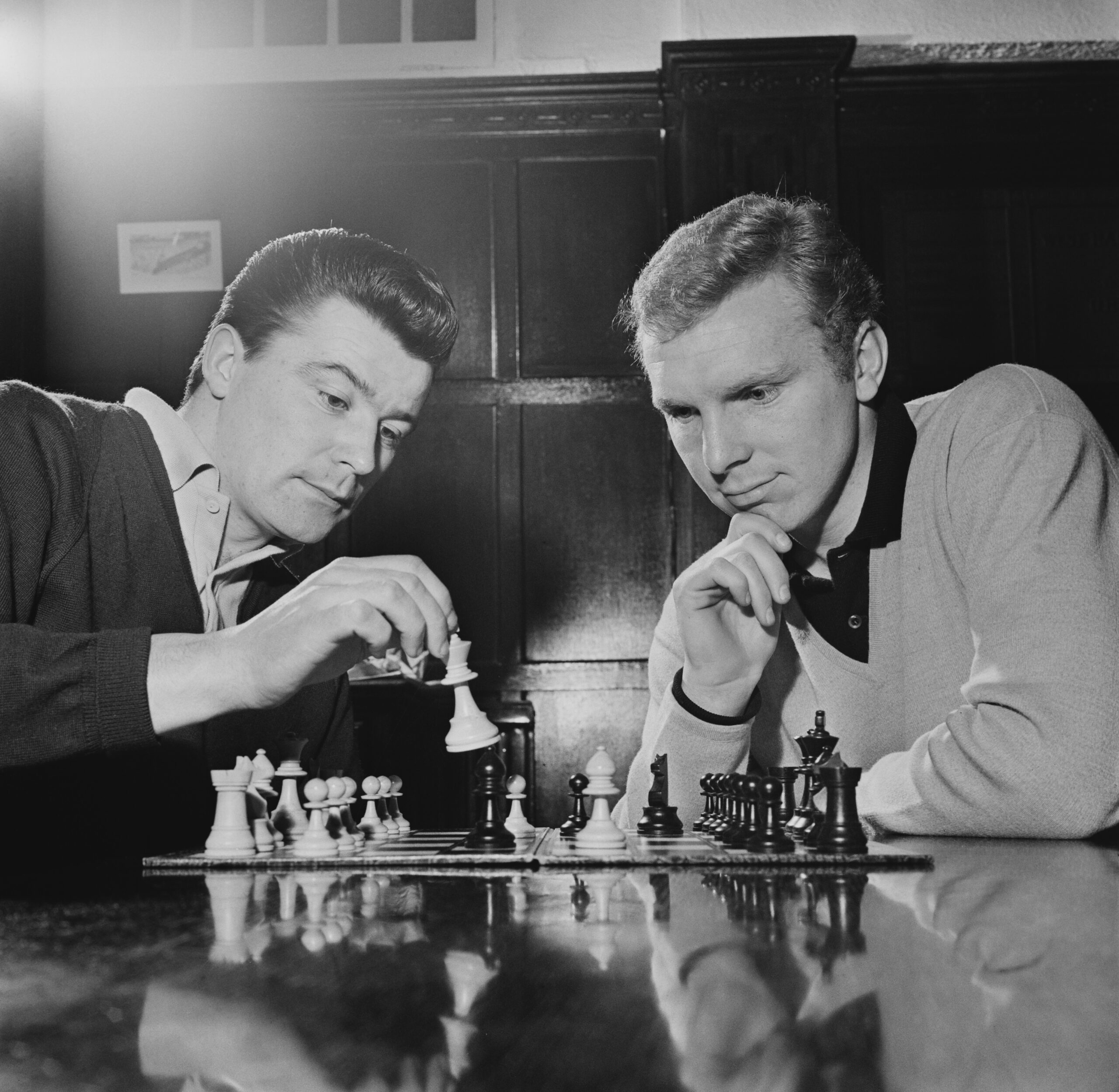

This got me thinking. Which sport has decision-making and tactical approaches, yet can be analysed with data? My eyes — pun intended — turned towards chess and the openings/defences you got there. In this article, I aim to translate, convert and surpass chess strategies and make them actionable for analysis.

This article will describe a few chess strategies and how we can look into them with data and create playing styles/tactics from them. The methodology will be a vital part of this analysis.

Contents

- Introduction: Why compare chess and football?

- Data representation and resources

- Chess strategies

- Defining the framework: converting chess into football tactics

- Methodology

- Analysis

- Challenges and difficulties

- Final thoughts

Introduction: Why compare chess and football?

First of all, I love comparisons with other disciplines. It gives us an idea of where we can improve from other sports and/or influence other sports. Until now, I have focused mostly on basketball and ice hockey, but there are other sports I want to have a look at: rugby, American football and baseball.

Truth be told, do I know a lot about chess? Probably not. I’m a fairly decent chess player, and I know the basic theory of strategies in chess, but you won’t find an ELO rating to be proud of you in my house. But that’s beside the point. The point is that I love chess for its tactics and strategies. It’s so prevalent in our language that we often call close-knit games: a game of chess.

My brain wanted to make a comparison between chess tactics and chess moves that can be seen in the light of certain actions and patterns in football. For that specific little research and to get the tactics, I am going to look at chess moves and relate them to passing in football. This will become slightly clearer in the rest of the article.

Data representation and sources

This remains a blog or website where I love to showcase data and what you can do with it. This article is no different.

The data I’m using for this is data gained from Opta/StatsPerform and focuses on the event data of the English Premier League 2024–2025. The data was collected on March 1st 2025.

We focus on all players and teams in the league, but for our chain events and scores, we focus on players that have played over 450 minutes or 5 games in the regular season. In that way we can make the data and, subsequently the results, more representative to work with.

Chess strategies

There are 11 strategies that I have found in chess that I found were suitable for analysis. Our analysis focuses on passing styles based on the chess strategies.

Caro-Kann Defense (Counterattacking, Defensive)

- Moves: 1. e4 c6 2. d4 d5

- A solid and resilient defense against 1. e4. Black delays piece development in favor of a strong pawn structure. Often leads to closed, positional battles where Black seeks long-term counterplay.

Scotch Game (Attacking)

- Moves: 1. e4 e5 2. Nf3 Nc6 3. d4. White aggressively challenges the center early. Leads to open positions with fast piece development and tactical opportunities. White often aims for a kingside attack or central dominance.

Nimzo-Indian Defense (Counterattacking, Positional)

- Moves: 1. d4 Nf6 2. c4 e6 3. Nc3 Bb4. Black immediately pins White’s knight on c3, controlling the center indirectly. Focuses on long-term strategic play rather than immediate counterattacks. Offers deep positional ideas, such as doubled pawns and bishop pair imbalances.

Sicilian Defense (Counterattacking, Attacking)

- Moves: 1. e4 c5 Black avoids symmetrical pawn structures, leading to sharp, double-edged play. Common aggressive variations: Najdorf, Dragon, Sveshnikov, Scheveningen. White often plays Open Sicilian (2. Nf3 followed by d4) to create attacking chances.

King’s Indian Defense (Counterattacking)

- Moves: 1. d4 Nf6 2. c4 g6 3. Nc3 Bg7. Black allows White to occupy the center with pawns, then strikes back with …e5 or …c5. Leads to sharp middle games where Black attacks on the kingside and White on the queenside.

Ruy-Lopez (Attacking, Positional)

- Moves: 1. e4 e5 2. Nf3 Nc6 3. Bb5. White applies early pressure on Black’s knight, planning long-term positional gains. Leads to rich, strategic play with both attacking and defensive options. Popular variations: Closed Ruy-Lopez, Open Ruy-Lopez, Berlin Defense.

Queen’s Gambit (Attacking, Positional)

- Moves: 1. d4 d5 2. c4. White offers a pawn to gain strong central control and initiative. If Black accepts (Queen’s Gambit Accepted), White gains rapid development. If Black declines (Queen’s Gambit Declined), a long-term strategic battle ensues.

French Defense (Defensive, Counterattacking)

- Moves: 1. e4 e6. Black invites White to control the center but plans to challenge it with …d5. Often leads to closed, slow-paced games where maneuvering is key. White may attack on the kingside, while Black plays for counterplay in the center or queenside.

Alekhine Defense (Counterattacking)

- Moves: 1. e4 Nf6. Black provokes White into overextending in the center, planning a counterattack. Leads to unbalanced positions with both positional and tactical play. It can transpose into hypermodern setups, where Black undermines White’s center.

Grünfeld Defense (Counterattacking, Positional)

- Moves: 1. d4 Nf6 2. c4 g6 3. Nc3 d5. Black allows White to build a strong center, then attacks it with pieces rather than pawns. Leads to open, sharp positions where Black seeks dynamic counterplay.

Pirc Defense (Defensive, Counterattacking)

Moves: 1. e4 d6 2. d4 Nf6 3. Nc3 g6. Black fianchettos the dark-square bishop, delaying direct confrontation in the center. Leads to flexible, maneuvering play, often followed by a counterattack. White can opt for aggressive setups like the Austrian Attack.

Defining the framework: converting chess into football tactics

A Caro-Kann Defense in chess is built on strong defensive structure and gradual counterplay, mirroring a possession-oriented style in football, where teams maintain the ball, carefully build their attacks, and avoid risky passes. On the other hand, the Scotch Game, an aggressive opening that prioritises rapid piece development and early control, aligns with high-tempo vertical passing. Teams using this style move the ball forward quickly, looking to exploit spaces between the lines and catch opponents off guard.

Some openings in chess focus on inviting pressure to counterattack, a principle widely used in football. The Sicilian Defense allows White to attack first, only for Black to strike back with powerful counterplay. This is akin to teams that play deep and absorb pressure before launching devastating transitions. Similarly, the King’s Indian Defense concedes space early before unleashing an aggressive kingside attack, where the team defended deep and then launched precise, rapid counterattacks.

Certain chess openings focus on compact positional play and indirect control, mirroring football teams that overload key areas of the pitch without necessarily dominating possession. The Nimzo-Indian Defense, for instance, does not immediately fight for central space but instead restricts the opponent’s development, where tight defensive structure and midfield control dictate the game. Likewise, the French Defense prioritizes a solid defensive structure and controlled build-up, where possession is carefully circulated before breaking forward.

Teams that thrive on wide play and overlapping full-backs resemble chess openings that emphasize control of the board’s edges. The Grünfeld Defense, which allows an opponent to take central space before striking from the flanks. In contrast, teams that bait opponents into pressing only to bypass them with quick passes follow the logic of the Alekhine Defense, which provokes aggressive moves from White and counters efficiently.

The flexibility of the Pirc Defense, an opening that adapts to an opponent’s approach before deciding on a course of action, can be likened to teams that switch between possession play and direct football depending on the game situation. The adaptability of this approach makes it unpredictable and difficult to counter.

Methodology

So now we have the strategies from chess that we are going to use for the analysis, and we know how they resemble similar football tactics already. The next step is to look at existing data and see how we can derive the appropriate metrics to design something new in football.

From the event data we need a few things to start the calculation:

- Timestamps

- x, y

- playerId and playerName

- team

- typeId

- outcome

- KeyPass

- endX, endY

- passlength

First, individual match data is processed to extract essential passing attributes such as pass coordinates, pass lengths, and event types. For each pass, metrics like forward progression, lateral movement, and entries into the final third are computed, forming the building blocks of the tactical analysis.

Once these basic measures are derived, seven distinct metrics are calculated from the passing events: progressive passes, risk-taking passes, lateral switches, final third entries, passes made under pressure, high-value key passes, and crosses into the box. Each metric captures a specific aspect of passing behavior, reflecting how aggressively or defensively a team approaches building an attack.

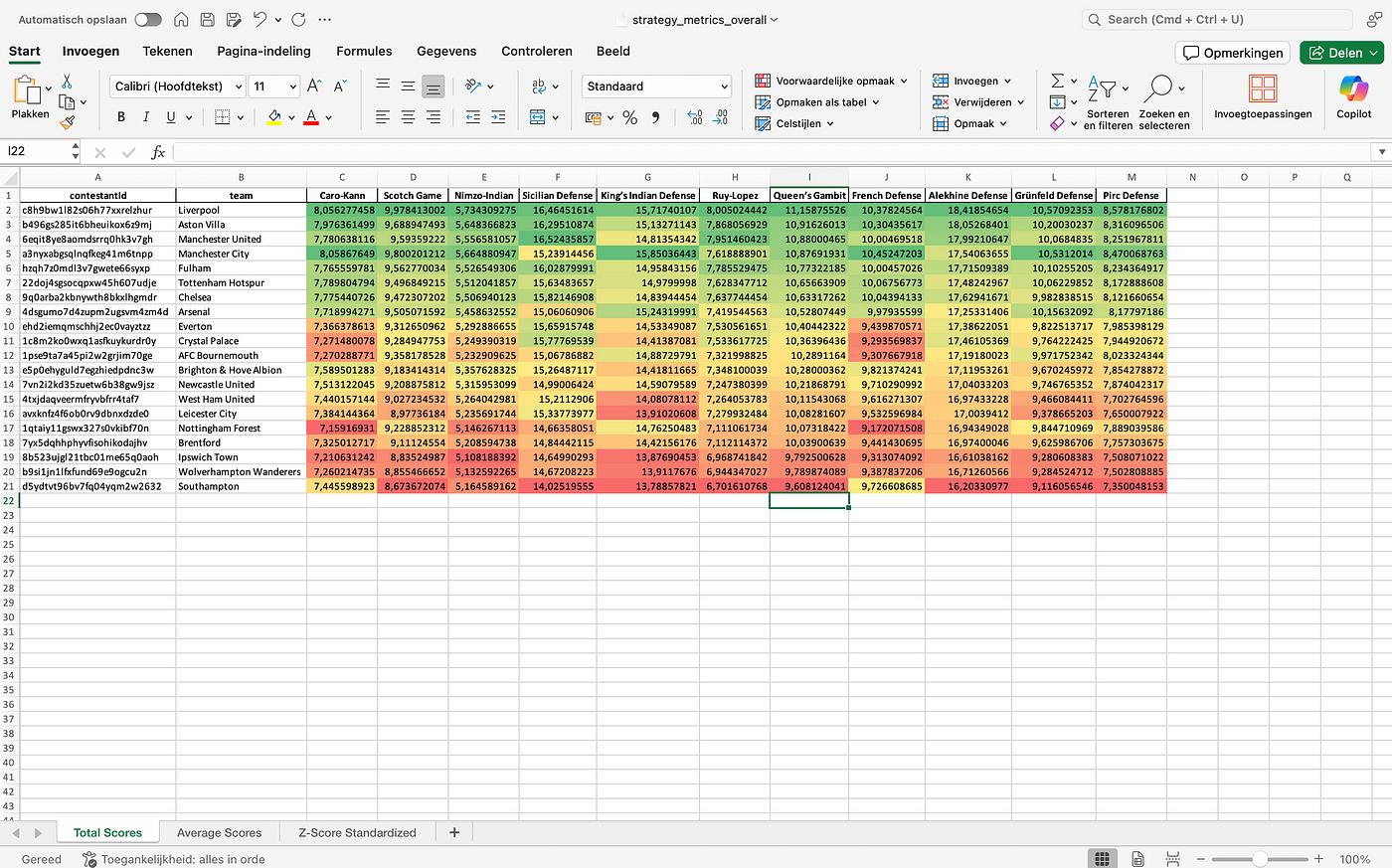

For every tactical archetype — each modeled after a corresponding chess opening — a unique set of weights is assigned to these metrics. The overall strategy score for a team in a given match is then computed by multiplying each metric by its respective weight and summing the results. This weighted sum provides a single numerical value that encapsulates the team’s tendency towards a particular passing style.

Strategy Score=w1(progressive)+w2(risk-taking)+w3(lateral switch)+w4(final third)+w5(under pressure)+w6(high-value key)+w7(crosses)

You can find the Python code here.

Analysis

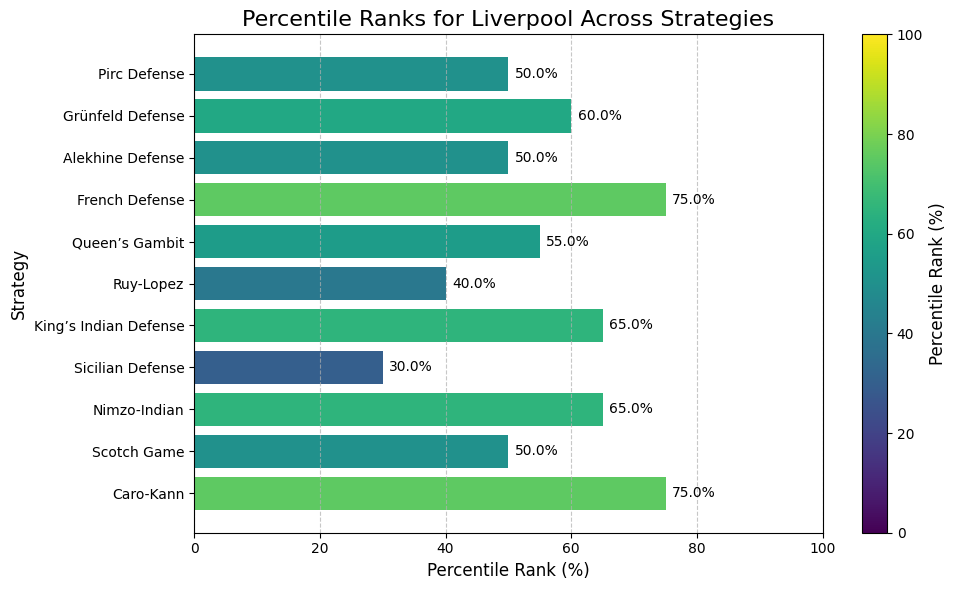

Now, with that data we can do a lot of things. We can for example look at percentile ranks and see what the intent is of a team regarding a specific style:

We can see how well Liverpool performs in the strategies coming from chess, and that leads to a shot. This shows us that the French Defence and the Caro-Kann are two strategies wherein Liverpool scores the best in, in relation to the rest of the league.

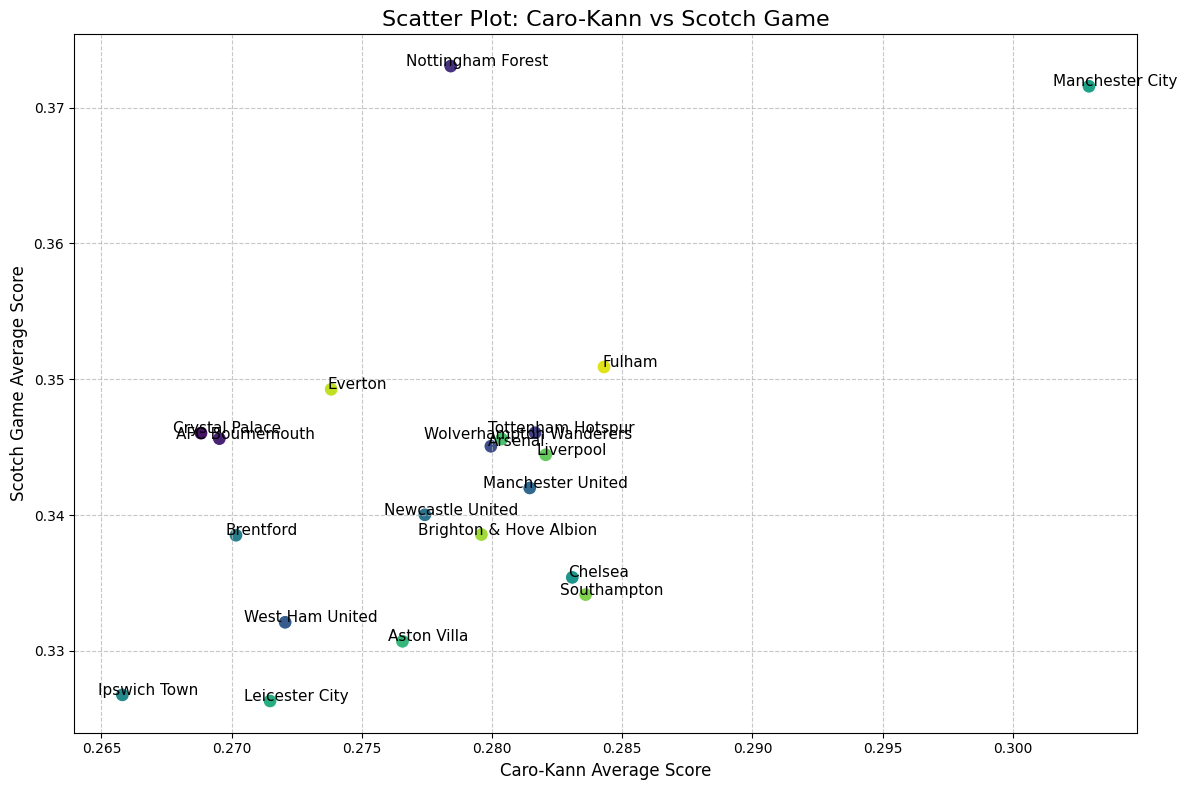

The next thing we can do is to see how well Liverpool in this case does when we compare two different metrics/strategies.

In this scatterplot we look at two different strategies. The aim is to look at how well Liverpool scores in both metrics, but also to look at the correlation between the two metrics.

Liverpool perform in the high average for metrics, while Nottingham Forest and Manchester City are outliers for these two strategies — meaning that they create many shot above average from these two strategies.

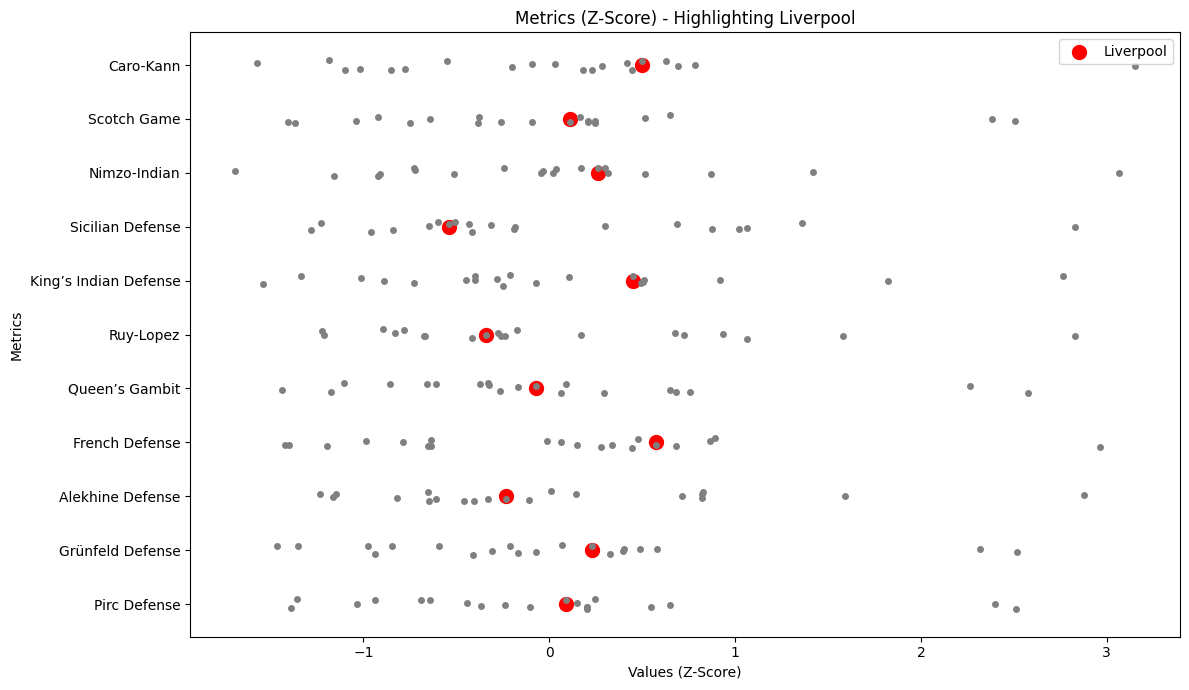

Anothre way of visualising how well teams are creating shots from certain tactical styles adopted from chess, is a beeswarm plot.

In the visual above you can see the z-scores per strategy and where Liverpool is placed in the quantity of getting shots. As you can see they score around the mean or slight above/under the mean with small standard deviations. What’s important here is they don’t seem to be outliers in both the positive or negative way.

Challenges

- Chess moves are clearly categorised, but football actions depend on multiple moving elements and real-time decisions.

- Assigning numerical values to football tactics is complex because the same play can have different outcomes.

- In football, opponents react dynamically, unlike in chess where the opponent’s possible responses are limited.

- A single football tactic can have multiple different outcomes based on execution and opponent adaptation.

- There is no single equivalent to chess move evaluation in football, as every play depends on multiple contextual factors.

Final thoughts

Chess and football might seem worlds apart — one is rigid and turn-based, the other a chaotic dance of movement and reaction. Chess moves have clear evaluations, while football tactics shift with every pass, press, and positioning change. Concepts like forks and gambits exist in spirit but lack the structured predictability that chess offers. And while chess follows a finite game tree, football is a web of endless possibilities, shaped by human intuition and external forces.

Bridging this gap means bringing structure to football’s fluidity. Value-based models like Expected Possession Value (EPV), VAEP, and Expected Threat (xT) can quantify decisions much like a chess engine evaluates moves..

Reinforcement learning and tactical decision trees add another layer, helping teams optimize play in real-time. Football will never be as predictable as chess, but with the right models, it can become more strategic, measurable, and refined — a game of decisions, not just moments.

Geef een reactie